NEW YORK — Amid newly imposed tariffs on China, one spiritual wares store selling feng shui products in Chinatown fears the closure of longtime neighborhood establishments. A pack of noodles could increase by at least a dollar. The cost of takeout containers could hike up delivery prices.

Overall, businesses in Chinatown neighborhoods nationwide, which are particularly import-heavy, are looking at a potential 8% increase in prices.

But tariff fears are not just about financial concerns. In Chinatowns across the country, people worry about the loss of cultural traditions and the already high rates of poverty in these largely immigrant communities. In New York City, for example, 28% of Chinatown residents live below the poverty line.

Chinatowns contends with a unique crisis because many of the items sold there aren’t often available on mainstream platforms like Amazon. And there’s simply not enough demand for them for companies to build factories in the U.S.

Trump added a 10% tariff on all imports from China this week on top of a previous 10% tariff he had imposed on Chinese goods last month. These are in addition to tariffs of up to 25% Trump imposed during his first term. He said the import taxes, which he also imposed on Canada and Mexico before temporarily pausing them, will be in place until China takes action to reduce the flow of fentanyl into the U.S.

China has retaliated by imposing tariffs of its own on the U.S., adding up to 15% on some U.S. goods.

“The Chinese people have never believed in coercion or intimidation, nor do we succumb to bullying and hegemonic tactics,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian said during a Tuesday briefing.

Many of the stores in Chinatowns across the U.S. source the majority of their items from China. Wing On Wo & Co. in New York City, for example, gets 90% of its goods from the country. Lining the shelves are porcelain and ceramic wares, from ornate patterned serving trays to incense holders shaped like bok choy leaves. Fifth-generation store owner Mei Lum said much about the store’s business strategy, particularly during its busy season around Lunar New Year and Christmas, is now uncertain.

NBC News spoke to more than half a dozen shop and restaurant owners who said these communities, as they have done in the past, are intent on finding a way to endure.

“Something that I’m holding on to is that folks in Chinatown are really resourceful. They’re really innovative,” Lum said. “They figure out ways to support each other.”

Kenny Li, who has run the Asian home goods shop K.K. Discount Store in Manhattan’s Chinatown for over 30 years, said that alongside rising rent and overhead costs, tariffs add to a long list of issues that have made it difficult for mom-and-pop shops around the neighborhood to stick around. It’s no wonder, he said, that stores like his are disappearing.

“Right now, this kind of store, they don’t have more than two,” Li said. “So many people who were open 20, 30 years ago have retired. … They say they cannot lose money.”

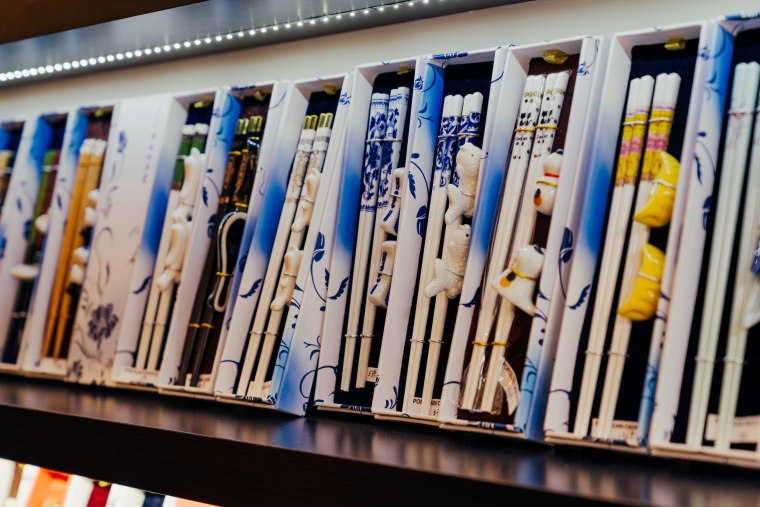

Just a few minutes’ walk from K.K. Discount is Yùnhóng Chopsticks, a small gift shop that gets most of its products from China. Bing Lü, who runs the business with his family, said they’ve had to add a 3% credit card fee on purchases just to help cover expenses, and they expect to raise prices a bit more due to tariffs.

What will the tariffs on China look like?

Chris Tang, a professor at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management whose area of expertise is global supply chain management, explained that when it comes to Chinatowns, people often rely on the enclaves for products that aren’t easily accessible elsewhere. While some supporters think tariffs encourage domestic production, that isn’t the case with many cultural items, Tang said.

“The volume is too small, and it’s really only this Chinese population who will buy them. So there’s no way for them to create factories to make it in the U.S. The scale is not big enough,” Tang said. “So it’s certainly the case that they have to import. There’s no way out.”

Tang added that consumers likely won’t feel the full impact of the tariffs immediately, as it takes a few weeks for the taxes to reach the retail level.

Lum’s store, which opened in 1925 and remains the longest-operating establishment in Manhattan’s Chinatown, sources most of its goods from Jingdezhen, a city in southern China widely known for its porcelain. She said she’s already seeing some of the effects of the tariffs, having received a retroactive invoice this week that likely includes tariff-related fees for a shipment from last month. And there’s a lot of confusion around how these fees are calculated.

“Our working-class community here in Chinatown is definitely, in these circumstances, always being hit the hardest,” Lum said of the neighborhood’s small business owners. “And a lot of them have told me that their solution to mitigating these circumstances has been to eat those costs and only raise those prices by a smidgen, just to make sure they’re affordable for the people that frequent their establishments. … How long can they sustain that?”

Working-class families depend on Chinatown for its low costs

The comparatively low prices in Chinatowns across the country are largely meant to serve lower-income and working-class families, locals pointed out. In New York City, the neighborhood’s median income of $35,805 is significantly lower than that of Manhattan as a whole, at $86,553. A few hours away, in Philadelphia’s Chinatown, the poverty rate hovers around 32%.

Xu Lin, owner of the restaurant Bubblefish in Philadelphia’s Chinatown, said the tariffs could force the enclaves to change their historically low-price image. Takeout containers and other goods that are central to everyday operations are sourced from China, Lin said. Consumers’ pivot to delivery apps has already forced restaurants to fork over sizable fees to these companies, cutting into profits, he said. Rising prices have resulted in an almost immediate drop in sales, he said. But he may have no choice but to raise them further with the tariffs.

“Years and years after Covid, a big portion of our sales still come from delivery sales,” Lin said. “If our takeout containers continue to increase, then we’ll be forced to increase our delivery.”

Across the country in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Shelby Wu, who grew up there and now runs the newly opened cafe Fruitful Dreams, said many immigrants in the area have already made financial sacrifices and the tariffs are sure to compound the strain.

“Most of us, including myself, my family, come from a very low-income background. … And we do actually rely on affordable and good products in Chinatown,” Li said. “People just don’t feel the same way anymore. They feel like they lost that type of resource that they used to have.”

Businesses are fighting against cultural loss

Many Chinatown business owners also voiced concerns about the preservation of culture. Lucas Li’s family runs Lion Trading in San Francisco’s Chinatown, which sells imported feng shui products and Buddhist and other spiritual supplies. He said age-old practices that involve imported goods could change. His store, for example, sells joss papers and other ceremonial items that are burned during funeral rituals or other occasions to honor ancestors. Younger generations are already shifting away from these practices, and tariffs could mean more loss.

“When they get expensive, it makes it harder for Chinese people, for their families to maintain those traditions and do it at the proper steps,” Li said of these ceremonial items. “When customers shop at local businesses and small businesses, they’re not just buying a product, they’re basically investing in the community and supporting families and protecting our traditions.”

Unfortunately, he said, several stores in the area have made the decision to shutter within the next two years, doubtful they can outlast the Trump tariffs.

Wu, whose store sells candied fruit skewers known as “tanghulu” that require special pots and equipment from China to cook, also said authenticity is at stake.

“Most of the businesses here will have to rely on American resources, which could be a little bit different than what we can get from China,” Wu said. “We might have to change a bit of the way we usually make our traditional foods.”

Given the Trump administration’s “America First” policies, Tang said, it will be an uncertain undertaking to celebrate and honor the diverse cultures across the U.S. — and it will be up to Chinese Americans to fight for their communities.

“If this is how he’s defined what America is, then the question is: Within this framework, would it be possible for different ethnic groups to preserve some of the identity for the historical perspective, for cultural perspective?” Tang said. “That remains to be seen, but I think we need more grassroots movement to protect that.”

Lum said that she has no doubt the community will come through.

“Chinatown has a really strong cultural fabric. We have been, for many generations, stewarding and growing and building upon what our ancestors, who founded Chinatown in the 1890s, have brought over,” Lum said. “We have to be creative, and I think that Chinatown and the folks here have proven that they can be in times of oppression.”