“Take a lesbian to lunch!” read one of the signs. “Women’s liberation is a lesbian plot,” said another, and “We are the people you are afraid of.”

It was 1970, and an event in New York City sponsored by the National Organization for Women (NOW) was being interrupted by dozens of lesbian feminists who surrounded the audience with demands to be heard, a direct action against being marginalized by the mainstream women’s movement.

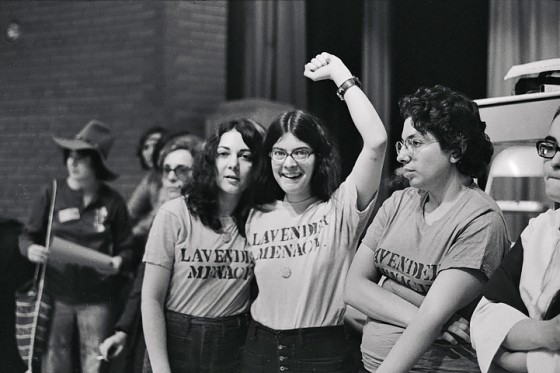

“I was dressed in a nice blouse. I stood up and I said, ‘Sisters, I’m so tired of being in the closet in the women’s movement. This is too much already.’ And I ripped my blouse off, and I had a ‘Lavender Menace’ T-shirt underneath,” said longtime LGBTQ activist Karla Jay, then 23 years old (and now 77).

Coining Lavender Menace Action for the protest was a reclamation of the inflammatory language used by NOW co-founder Betty Friedan, a complicated but early leader of the women’s liberation movement, whose 1963 book, “The Feminine Mystique,” is credited with sparking second-wave feminism. Friedan referred to lesbians as a “lavender menace” threatening to tarnish the women’s movement as a fringe group of “man-haters.”

The demonstrators, who called themselves the Radicalesbians, held the floor for hours and confronted audience members at NOW’s Second Congress to Unite Women about the group’s exclusionary practices and homophobia. While the protesters were small in number, they had an outsized impact, giving a face and a name to lesbian feminists. The group also passed out copies of its manifesto, “The Woman-Identified Woman,” which described lesbianism not as a side issue but as essential to the success of the women’s liberation movement as a whole.

It worked. The next year, in 1971, NOW passed a resolution recognizing the “oppression of lesbians as a legitimate concern of feminism,” though Jay said lesbians “were not accepted as equal partners” until 1977, when NOW passed its lesbian rights resolution. Last month, more than a half-century after the Lavender Menace protest, several of the women who participated reunited in New York City to share memories and offer their advice to activists today.

“Our movement is needed right here, right now,” said Flavia Rando, who not only was part of the group but also worked to wrestle gay bars out of the hands of the Mafia, which controlled the bars into the 1970s. “It’s really because we’re an easy scapegoat, an easy target. There’s kind of a gender hysteria in the country right now.”

A slew of laws have been passed targeting LGBTQ people in the last couple of years, with restrictions on gender-affirming care for transgender youths among the most common. But in the coming election, at least 18 out transgender candidates are running for seats in state legislatures, according to the LGBTQ Victory Fund.

“I know people are very happy with everything we’ve gained. Certainly it’s better than having to walk down the street looking down for fear of being attacked. But we’re very far from done,” Rando said.

The group gathered at the Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center, which is next door to the Stonewall Inn and was part of the iconic bar during the 1969 Stonewall uprising. Also in attendance was Lavender Menace protester Martha Shelley, now 80 years old, who danced to the jukebox. An early and influential participant in the gay liberation movement, Shelley spoke on the second night of the June 1969 rebellion.

“In every generation, you have to fight back,” said Shelley, who was born with the last name Altman but changed it in the 1960s because of government surveillance of the Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian rights organization in the U.S., of which she was a member. She also presided over the New York City chapter as president.

Shelley said her advice for activists today is twofold. Part one: “If you try, if you fight, you may lose, but if you don’t fight, you will certainly lose, and if you do fight, you have a good chance of winning.” And for part two? “Even in the worst of times, you don’t give up.”

She encouraged people to vote but also said it’s important to keep up the pressure for justice, economic equality and climate action.

Ellen Broidy, who stood with Shelley and the others both in 1970 and then at the visitor’s center, said she could still feel the energy from over a half-century ago. “It just gave me chills right now,” she said.

Broidy was one of the co-organizers of New York City’s first gay pride march in 1970, which was then called the Christopher Street Liberation Day march. Broidy said that while the new generation of activists are “not letting anybody slap them down,” she wishes they knew more about the work that was done decades ago.

“I wish they knew the history more, and I wish every now and again ... that they turn around and see who came before them, not in a kind of laudatory way, but in a way to acknowledge we all stand on the shoulders of those who came before us.”

Broidy’s fellow activist Karla Jay pointed out change was made back in the 1970s with a small group of people and said activists of today should be inspired by that.

“It didn’t matter that there were only 30 or 40 of us, and I think that young people today can do what they want and not be afraid that there aren’t enough of them to make social change. They have to have the courage of their convictions and go out and organize, and they have to decide what dream they want to follow,” Jay said. “Don’t follow my dream. I’m still marching, but I want them to pick up their own torches and march up the street, as well.”

Friedan eventually apologized for her use of the phrase “lavender menace,” but not until 1977. Years later, Jay said, Friedan stopped her in an elevator. “She said to me, ‘Karla, you caused me so much trouble.’ And I said, ‘Betty, you caused yourself all this trouble.’”